14 December 2018

Harmony, Fresh Air; Stuff Like That.

Artist Profile —Alex Gibbs

Every time I say this it feels like such a terrible cliché, but life in a big city like London really can take its toll. When just walking ten minutes to the shops can feel daunting, making the trip across town to see a friend can quickly become the insurmountable journey that inevitably, and repeatedly, gets postponed. So, in spite of the fact I live no more than one hour from his east London studio, it took a well timed escape to Norfolk for my friend Alex Gibbs and I to finally have the conversation we’d been progressively putting-off for over a year. What we needed was harmony, fresh air, to get out of it for a while—a welcome repose that Alex’s work is capable of delivering in more ways than one.

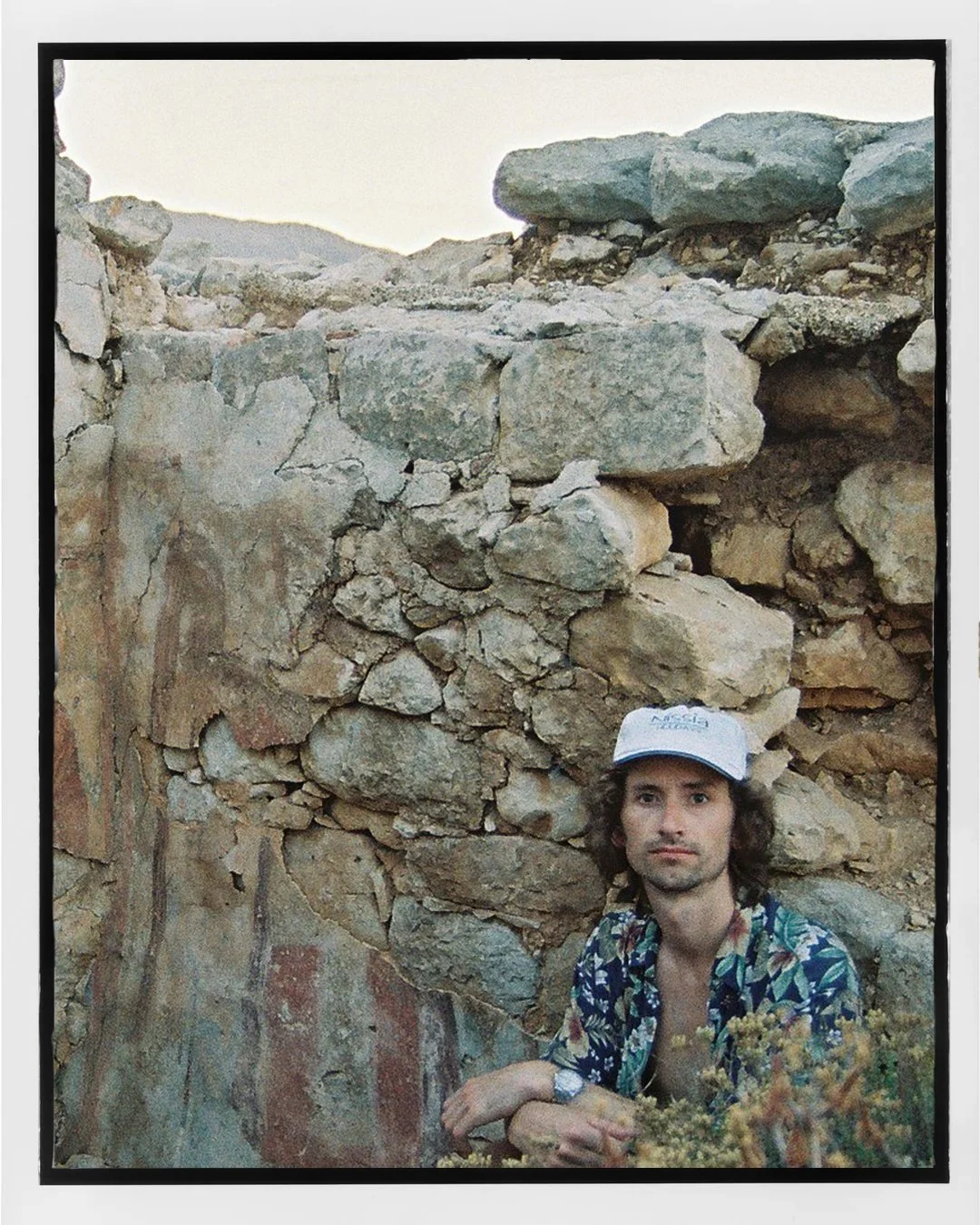

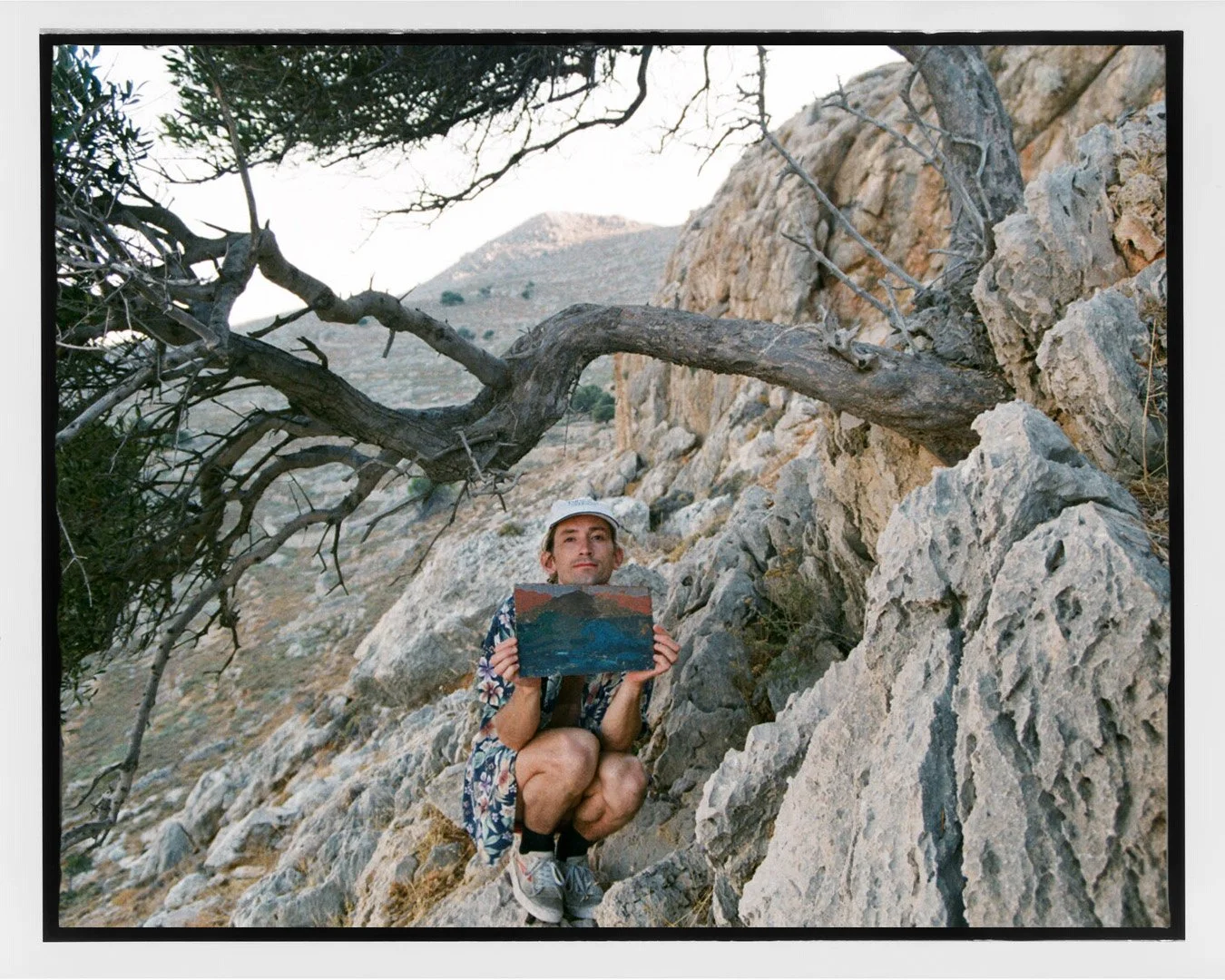

image courtesy of the artist

Alex is in Norfolk staying at his family farm house, Beach Farm, a flint-wall and thatched-roof haven just up the coast near Eccles-on-Sea; a regular refuge for he and his family, fair-weather and winter alike. I’m here visiting my girlfriend’s family, not far from the Norfolk Broads, at Cold Comfort Farm…just kidding, although I think she actually does have a cousin called Seth.

One sunny afternoon following the exciting discovery of our respective get-aways, Alex Gibbs met me at Horsey (one of the local beaches) with two push-bikes, a tweed cap for me to wear and a lifetime of local gossip and anecdotes to keep us entertained on the ride. Wheeling through the hedgerows—pilfering the last of the season’s blackberries between charming stories of murder at the caravan park, sordid affairs, and recipes for nettle soup—Alex tells me about a string of his recent shows, including one in Lairg, Scotland, displaying a series of hand-painted birthday cards he makes for his nearest and dearest. For years he’s been painting two for every occasion, gifting one and collecting their respective counterparts, soon to have their public debut on the banks of Little Loch Shin.

Title? etc.

As I write this, Alex is also exhibiting a small series of paintings at Bandwidth gallery in Anchorage, Alaska. This show, similar to that of the gift-card show in Scotland, brings together an unusual collection of paintings that Alex has been quietly accumulating over the years. On family trips to Greece—which he is amazed he is still invited to—Alex spends his afternoons making small, holiday paintings and leaves them hidden among the rocks on the island’s remote hilltops. Noting the coordinates and memorable landmarks, he makes the dusty pilgrimage to collect them the following year, marking time and the collaborative efforts of the wind and rain through the dramatic patina that builds on the painting’s surface.

There is an interesting trend emerging through Alex’s CV, as he boasts a string of ‘off-the-beaten-track’ exhibitions that seem to suit his work perfectly: the gift-cards exhibited in a tiny town in Scotland; the exhibition in Anchorage; and finally a recent group-show with two of his closest friends in Ballyvaughan—a quiet town on Ireland’s ‘best coast’ (inexplicable home to a world class art-school, Burren College of Art). The way Alex describes these ‘fringe’ shows, the incredible and often under-utilised gallery spaces, and the overwhelmingly warm reception they receive from the locals, I can’t help but question the perceived prestige of exhibiting in cities like London and the sort of work that seems to dominate the scene of emerging and early-career artists.

There is a kind of thematic melancholy and simplicity about Alex’s work that does suit a certain image of these ‘slower pace’ surroundings—offering one possible, albeit superficial, explanation for his choice to exhibit in these remote galleries. However, as a jaded city-dweller, I must be wary of drawing such comparisons, as it immediately relegates everything to a level of appreciation and experience that hardly feels worthy of reporting on; while unfairly conjuring a slightly hollow image of regional galleries. Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly, this equation does little to highlight the unexpected and complex influence I believe these locations and audiences have had on Alex’s work. There is a severely under-utilised recipe for development at play here, and it lies at the heart of Alex’s preferred audience themselves.

Like the Burren College of Art and his latest show at Bandwidth in Alaska, these remote locations in which Alex’s paintings find themselves are not only home to sensitive and artistic communities, they’re also, more often than not, attached to Art schools. In a way, Alex’s differently discerning and curious viewership becomes a sort of microcosm of a museum audience. A healthy mix of academics, artists, students, children and supportive townspeople that could fall into any number of categories, even down to the self-diagnosed laymen. In this sense, these exhibitions have become a valuable test of how one contextualises their work for an uncommonly diverse range of expectations—a test not often presented to young graduates of MA programs.

The minute you assume a certain level of understanding from your audience, or attempt to play to those expectations, you risk losing losing sight of the delicate art of democratic display—a deficiency that often goes undiagnosed or unacknowledged in smaller, independent galleries where perhaps the expectations and knowledge of their following can be more easily pigeonholed. It becomes art made for other artists.

In the face of this I have an increasing aversion to Contemporary art vernacular, and while I do really enjoy a well constructed academic concept or progressive piece of writing, more often than not I find that I struggle my way through gallery texts and artist statements, swallowing every overwrought sentence like Cool Hand Luke taking down those eggs. It’s troubling, the moment these impenetrable ideas and artworks are taken too seriously—and this assumption of our understanding is made—one quickly begins to see the insecure cracks in the walls, and the feigned attempts to obscure them with absurdly academic language and trite aesthetic techniques that have somehow become the default. Rather than encouraging and guiding me to better understand their ideas, I feel them slipping through my grasp, leaving me with a particular sense of frustration as it hints at an emptiness beneath the utterly fragile veneer.

I don’t feel this same sinking feeling when I look at Alex’s work. Whether it is the direct influence of these rural audiences or something inherent in Gibbs’ work that has been circumstantially induced, I’m certain that the act of showing in these regional galleries has allowed Alex to think about his work in a way that naturally appeals to multiple levels of appreciation. The titles that adorn his work are at once thoughtful, esoteric, humorous, lyrical and descriptive. His subjects emerge from the inner-workings and observations of an unquestionably odd individual, one who is able to see even the most absurdly innocuous experiences through a very peculiar and colourful lens. Painted and performed with a dedication to his craft, every brush stroke, colour, texture, composition, outfit, lyric, title, pose, even his mistakes, everything is a reflection of his uncompromising character. A character that, in spite of my obsequious flattery, can be as easily loathed as it can be loved, however it is always clear to see that his intentions are nothing if not sincere.

He lends you a nostalgia for some unremembered moment and invites you to submit to his whimsical performance that is somehow both uninhibited and completely insecure. Yet in spite of the complexity and the emotional potential of the world that Alex creates, these vibrant moments of poetic sincerity do hold the potential to be his undoing.When even his jumper looks like one of his paintings it would be easy to dismiss it all as being too much, too self-aware or contrived. But in these out-of-the-way exhibitions, everything is administered in such gentle doses that he allows you—and his sparsely hung paintings— significant room to breathe, room to find your own way though the quiet uncertainty. Just like the locations that these paintings now routinely inhabit, they provide a welcome respite from the noise of contemporary art in London.

Over the summer, Alex was invited to perform at the Elastic Friends’ sixth annual End o’ the Year Grub Up. A gallery dinner that routinely invites, “artists who sing” to perform as the evening’s entrainment. In lieu of attending the sickeningly cool event, I was one of the lucky few blessed with a sneak preview of some of the music he’d written and recorded in the lead up to the dinner. I’m not sure what it was, but something about the earnestness and vulnerability of the song had me welling up—a stark contrast in reaction compared to those in the room who found it completely hilarious, perfectly illustrating this uncertain realm between sincerity and a knowing, conspiratorial wink that Alex manages to navigate so artfully.

Sipping cask ale at a picnic table in the garden of The Nelson Head, we sit and look out across vast and verdant fields, all bordered to the north-east by a neatly constructed sea wall—a feat of human engineering almost as impressive as the knitted sweater that Alex is wearing.

My afternoon with Alex left me brimming with ideas, dying to recount every charming detail to anyone who would listen. Moreover, it left me determined to champion artists who, like this softly spoken Scotsman, nurture as much as they challenge. Alex Gibbs’ artwork fulfils a desire to dive into the late-night-blue-light, seeking the weird and wonderful from our pop-cultural depths, while simultaneously surrendering you to the anodyne innocence of a bird catching the morning’s first worm. Like any artist, Gibbs can’t please everyone. However, he doesn’t make you feel hopeless if you don’t like it or get it, and unlike many, he offers numerous ways in. Whether you’re passing through Alaska or catching one of his rare appearances in the city, just breathe deep, relax and surrender to a different pace of art—it might do you some good.